|

| David Brooks |

I'm a liberal Democrat, so my fear is more for the future of our country. It boggles my mind how an America which had made such great strides in the fight for racial justice, during my 70-year-and-counting lifetime, has now had such a profound racial relapse — witness the recent martyrdom of Heather Heyer in Charlottesville in a counter-protest against white supremacists who were themselves protesting the removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee.

|

| Jean Jaurès |

Jaurès was a leader among France's (and Europe's) socialists of his day. Though born into a bourgeois family in decline, and thus not of the proletariat or working class, Jaurés became the champion of the workers who toiled for too little pay in coal mines and factories. He insistently supported their right to unionize and strike for better wages and working conditions. His anti-militarism was born in part of his realization that many, many of France's proletarian class would die in a nationalist war with Germany.

Now, fast forward to the America of today. The No. 1 nonfiction/general bestseller is currently Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis, by J.D. Vance. The people Vance describes, and himself comes from, are families who earlier moved from Appalachia's coal country to places like Middletown, Ohio, to get jobs. In both places they were/are working-class, i.e., of the proletariat. Today, many of these people are out of work, but they once had decent-paying jobs in places like automobile factories.

Their current situation, though, is dire. Vance describes their situation as mainly one of cultural disintegration. It's a lot worse than just not having jobs any more. There are numerous symptoms of social dysfunction: family dissolution, alcoholism, drug dependency, etc. Wikipedia says Vance "feels that economic insecurity plays a much lesser role" in their misfortunes than the social rot does.

Maybe so. But a lot might improve for these erstwhile Appalachian members of America's "proletariat" if they had a champion from the political left, à la Jean Jaurès, who could fight for better economic conditions on their behalf.

In America today, many of our working-class citizens who saw Donald Trump as their champion became the decisive factor in giving him enough Rust Belt electoral votes to put him in the White House in the 2016 election. This shouldn't have happened. But there was no Jaurès to act as a working-class champion from the political left.

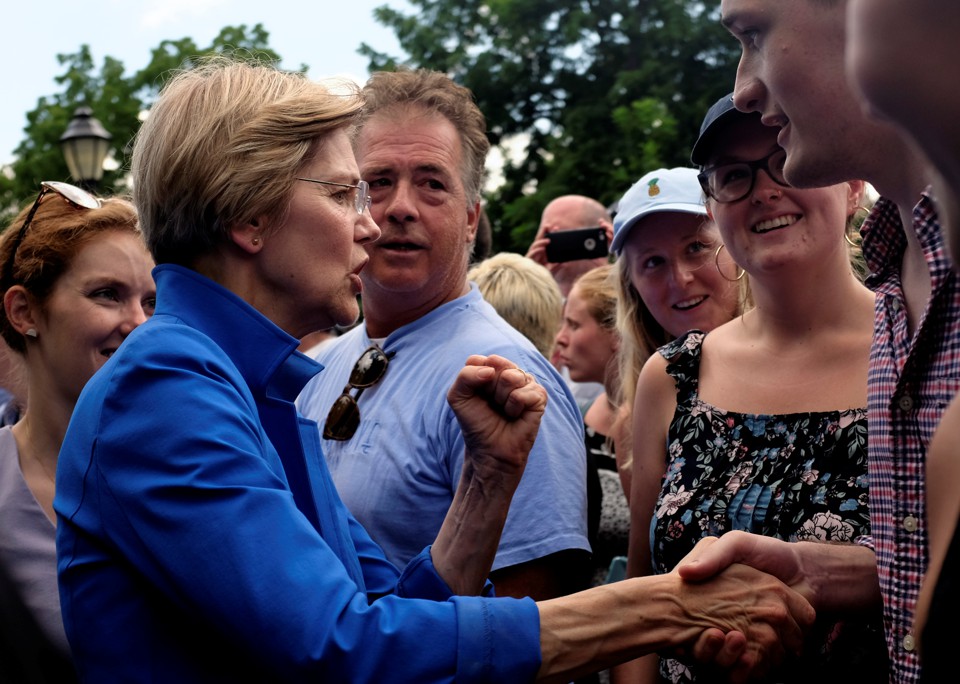

Hillary Clinton did not do and say the things that might have made her their champion. Bernie Sanders came closer than Clinton in his rhetoric and policy proposals, but Bernie did not capture the imaginations of the white working class. Other Democrats, such as Elizabeth Warren, are offering policies that would benefit this group of left-behind people, but her image does not resonate with them the way that Jaurès' image resonated with the workers of France. So it was left to Trump, a supreme charlatan, to do all the resonating.

Why don't the subjects of "Hillbilly Elegy" find a true champion on the left? I think a fundamental reason is that in the minds of many Rust Belt voters, white identity politics outweigh the economic policies offered by Clinton, Sanders, Warren, et al. — policy proposals that might boost these Americans' chances of gaining better jobs and richer lives.

In short, in America today race "trumps" class as a decider of elections. Even the great Jean Jaurès might not have been able to overcome that ugly truth, were he to be living in America today.