New York Times columnist Paul Krugman has recently been saying that the election was "hacked" by Russian intrusion into Hillary Clinton's campaign's emails. That was the source of items leaked by WikiLeaks that surely hurt Hillary's vote totals in crucial states. FBI Director James Comey didn't help when he sent a letter to Congress announcing that maybe, just maybe, new and incriminating emails that were on her private server when she was secretary of state had been found on a laptop of one of her main aides, Huma Abedin. Comey later backtracked and said no new or incriminating emails were found, but by then the damage was done to Hillary's electoral chances.

Mr. Krugman adds in another column that what's happening now in America resembles the lengthy run-up to the end of the ancient Roman Republic that culminated in the rise of a dictator named Julius Caesar.

I think Krugman is right, but I also think there were deeper reasons why Hillary lost the electoral vote even as she won the nationwide popular vote by some 2.8 million votes.

Each state has a number of electoral votes equal to its number of members of Congress: two U.S. senators plus the number of people it elects to the House of Representatives. For example, my state of Maryland has eight U.S. representatives, so its electoral votes total 2 + 8 = 10. (The District of Columbia has three electoral votes.)

All of each state's electoral votes are supposed to go to the presidential candidate who gets the most popular votes in that state. A few of the electors — the members of the Electoral College — yesterday violated that rule and voted for someone other than their state's popular-vote winner. But those few violations did not change the outcome which made Donald Trump officially the president-elect.

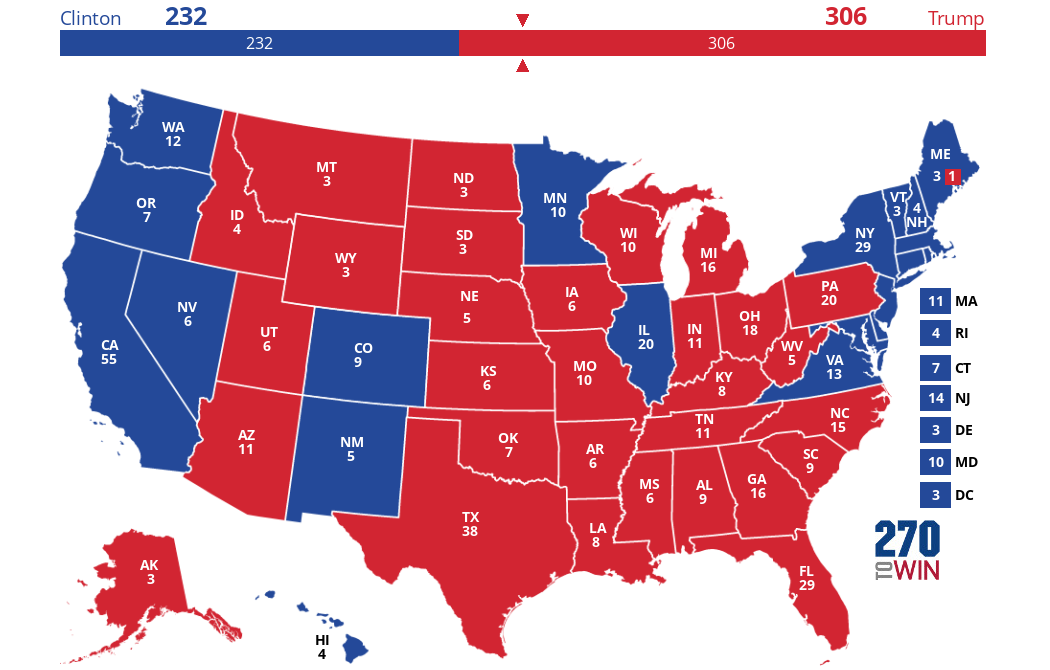

One of the many deeper reasons why the national top vote getter, Clinton, lost to Trump in the Electoral College is that her voters were for the most part tightly clustered into a few metropolitan areas in a relatively tiny number of states. Here's the 2016 electoral map:

Other than Nevada, Colorado, New Mexico, Minnesota, and Illinois, her blue states were all on the East Coast or West Coast. (I'm counting all of New England, including Vermont, as coastal. Hawaii is, in a sense, also coastal.)

One feature of most of the blue states is that they have big cities that are ringed by populous metropolitan areas. Many of the residents of the cities are nonwhite, and nonwhites voted heavily for Hillary. Meanwhile, many of the white residents of the cities and the surrounding metropolitan areas are cosmopolitan and liberal, and also voted for Hillary.

But in and around many Rust Belt cities and in non-metropolitan parts of the country the populace is often white, working-class, and non-cosmopolitan. Their votes served to turn their states red.

Illinois was one of the few non-coastal blue states this year. It was blue largely because of Cook County in the northeast part of the state which contains Chicago:

The state of Virginia went for Clinton largely due to populous urban areas such as the counties in the northeast part of the state that are suburbs of Washington, DC:

|

| (Green areas indicate partial results.) |

Get the idea? The reddest areas in the country were mostly places where there is a uniformity of ethnicity and class: specifically, white working-class. Other places tended to go blue.

A huge problem is accordingly the fact that in recent decades there has been an ongoing trend — among white Americans specifically — of pulling apart geographically in such a way that ZIP codes that were once diverse in income and economic class have become much less diverse. This is the thesis of political scientist Charles Murray (decidedly a conservative) in his book Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960-2010. National Review's "Essential Gift Guide 2016" said of the book:

In Coming Apart, Charles Murray explores the formation of American classes that are different in kind from anything we have ever known, focusing on whites as a way of driving home the fact that the trends he describes do not break along lines of race or ethnicity.

Drawing on five decades of statistics and research, Coming Apart demonstrates that a new upper class and a new lower class have diverged so far in core behaviors and values that they barely recognize their underlying American kinship—divergence that has nothing to do with income inequality and that has grown during good economic times and bad.

The top and bottom of white America increasingly live in different cultures, Murray argues, with the powerful upper class living in enclaves surrounded by their own kind, ignorant about life in mainstream America, and the lower class suffering from erosions of family and community life that strike at the heart of the pursuit of happiness. That divergence puts the success of the American project at risk.

The evidence in Coming Apart is about white America. Its message is about all of America.

Though Mr. Murray examines just white America in his book, it's clear from this year's election results that all of America — that is, whites and nonwhites, of various social and economic classes — has indeed "come apart" politically. This is one strong reason why the popular vote and the electoral vote pointed in different directions this year, just as they did in 2000 when Democrat Al Gore won the popular vote but lost the presidential election to Republican George W. Bush.

If white America had as much mixing of economic classes, geographically speaking, as it did in 1960, there would be fewer solid-red ZIP codes, counties, and states. Whites of various political persuasions would rub shoulders with one another. Chances are the constant interaction would make all affected individuals feel more a part of a common socioeconomic whole. That would tend to make them more moderate than the extreme political attitudes white working-class voters demonstrated this year.