|

| Hugh Hefner in 1966 |

I expect my father was one of the original subscribers to Playboy. I don't really remember for sure, though, whether he had the first issue, that of December 1953, with Marilyn Monroe on the cover:

|

| The December 1953 premiere issue of Playboy |

I was only six years old at the time, but by the time I was nine or ten, Dad was letting me peruse the Playboy issues stacked up on a shelf in our house.

I didn't understand then how radical Playboy was. I realized, of course, that photos of buxom young women in the nude were its main attraction, but I didn't know that just a few years prior, no mass-circulation magazine would ever have tried that.

After Hef died, Washington Post columnist Alyssa Rosenberg wrote:

On some major social issues, Hefner was early to take what are today mainstream progressive stances. ... Hefner was an early and avid defender of the gay rights movement, arguing that sexual liberation had to include gay people, too, in order for it to be meaningful. The same instincts led Hefner to publish extensive coverage of the emerging AIDS epidemic, recognizing that a sexually transmitted disease had no sexual orientation.

Hefner threw racially integrated parties in decades when it was not always popular to do so. Playboy picked its first black Playmate in 1965. And his magazine helped jump-start the writer Alex Haley’s career by asking him to interview Miles Davis, and Playboy then gave Haley an entire series, which eventually would include important interviews with Malcolm X and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

But her praise was not unalloyed:

Hefner may have advocated for women’s equality and independence in the political sphere. But that ideal state of affairs never arrived in Hefner’s lifetime, despite his advocacy for it. And Hefner’s own relationships were not necessarily defined by an equal balance of power.

New York Times columnist Ross Douthat was downright scathing:

Hugh Hefner, gone to his reward at the age of 91, was a pornographer and chauvinist who got rich on masturbation, consumerism and the exploitation of women, aged into a leering grotesque in a captain’s hat, and died a pack rat in a decaying manse where porn blared during his pathetic orgies.

Hef was the grinning pimp of the sexual revolution, with quaaludes for the ladies and Viagra for himself — a father of smut addictions and eating disorders, abortions and divorce and syphilis, a pretentious huckster who published Updike stories no one read while doing flesh procurement for celebrities, a revolutionary whose revolution chiefly benefited men much like himself.

That's unseemly and unfair. It misreads the Hefner legacy by judging it by the feminist and post-feminist standards of today — an ethos that could not have emerged at all in the 1960s absent what Hef did in the 1950s.

In 1948, researcher Alfred C. Kinsey and two other authors published the first of two "Kinsey Reports." Called Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, it would be followed in 1953 by Sexual Behavior in the Human Female.

These reports documented statistical studies that Kinsey undertook to find out what sorts of sexual behavior people were actually engaging in. The reports showed that in addition to the licit types of sexual behavior, there was a surprising amount of nominally illicit sex of various types going on.

My parents kept a copy of at least the Human Male report on a bookshelf, and at some point in my late childhood or early adolescence I pulled it off the shelf and looked it over. I doubt I understood much of it, but I did at least realize that it was telling the world about the ubiquity of sexual expression in our culture.

By 1960, when the first birth control pill was introduced, we were embarking on a sexual revolution, thanks in part to Alfred Kinsey and High Hefner.

|

| Betty Friedan |

By the late 1960s, Friedan's second-wave feminism was rocketing skyward among my female age peers. There was a supposed "bra burning" in 1969 that protested the Miss America contest in Atlantic City, Apparently, no bras were actually burned, but the event nonetheless ushered in an era in which feminists would conscientiously refuse to wear bras.

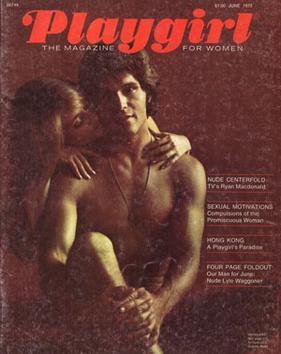

In 1973, Playgirl magazine appeared:

|

| First Playgirl issue, June 1973 |

It, too, had a centerfold. The first one was Lyle Waggoner, of the "Carol Burnett Show" on TV:

|

| Lyle Waggoner as the first Playgirl centerfold |

So it was a time when sexual liberation and feminism were intertwined. That's not so true now ... but I think the late Hugh Hefner is owed a vote of thanks, anyway!

No comments:

Post a Comment