|

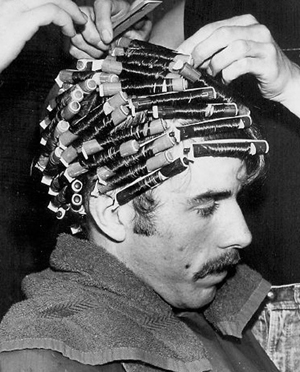

| David Brooks |

My favorite op-ed writer, David Brooks of

The New York Times, believes we have run off the tracks. In the Donald Trump era, our politics has gotten downright depraved. What's Mr. Brooks' solution? Hint: It's not just to keep lambasting Trump, his supporters, his policies, his personal behavior, etc.

In "

Personalism: The Philosophy We Need," Mr. Brooks talks about a philosophical movement that tells us "people are always way more complicated than you think." That's why stereotyping, even of Trump and his supporters, is always bound to come up short. It's just a shorthand we all tend to use, but it doesn't really represent who any of us is. "We talk in shorthand about 'Trump voters' or 'social justice warriors,' but when you actually meet people they defy categories. Someone might be a Latina lesbian who loves the N.R.A. or a socialist Mormon cowboy from Arizona."

Personalism was advocated by the likes of the Polish cardinal Karol Józef Wojtyła. We know him better by his later name, Pope (now Saint) John Paul II. The big idea here, writes Brooks, "is a philosophic tendency built on the infinite uniqueness and depth of each person. Over the years people like Walt Whitman, Martin Luther King, William James, Peter Maurin and Wojtyla ... have called themselves personalists."

I'm not 100% convinced by the personalist outlook, but I do believe it's worth considering. One reason I'm not totally convinced is that personalism draws a bright line between humans and animals. Brooks: "Personalism starts by drawing a line between humans and other animals. Your dog is great, but there is a depth, complexity and superabundance to each human personality that gives each person unique, infinite dignity."

(I seem to recall overhearing my cats saying to one another, "Our human servant is great, but there is a depth, complexity and superabundance to each feline personality that gives each cat unique, infinite dignity.")

OK, maybe that's a stretch. But I'm not so sure that biological evolution has made individuals of our species unique in having souls.

Anyway, I admit that the personalism advocated by David Brooks definitely makes a good jumping off point for our indeed treating one another as possessing "infinite uniqueness and depth."

*****

Yet I'd prefer shifting it over to something I'll call "relationalism." Relationalism is the idea that the world is not, as we usually think, made up first and foremost of hard-and-fast physical entities and then, only secondarily, the relationships these entities may establish among themselves.

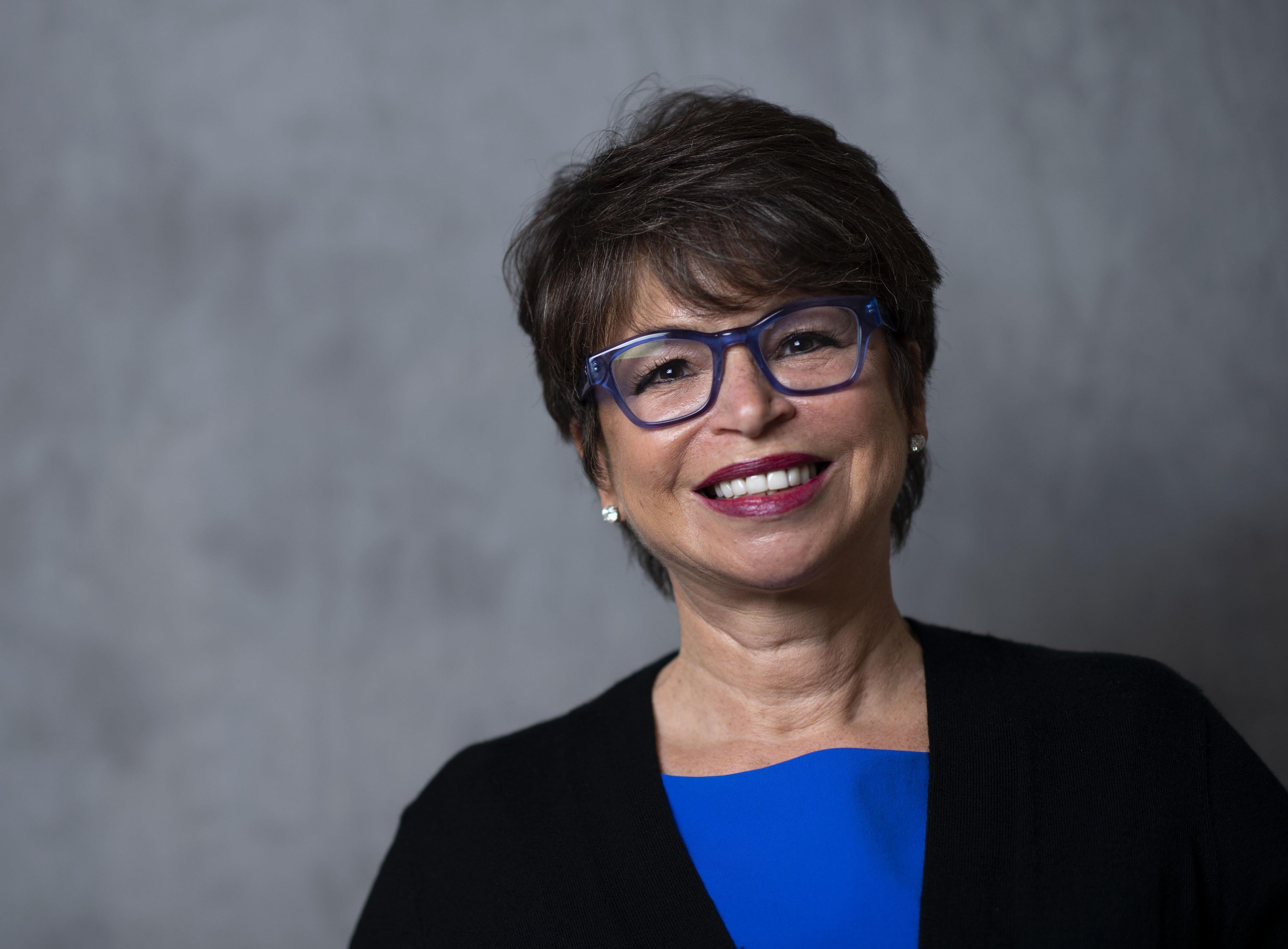

|

| Carlo Rovelli |

I take this idea from, among other sources, an episode of Krista Tippett's National Public Radio podcast "

On Being." The episode is "

All Reality Is Interaction," and it's an interview with physicist Carlo Rovelli. Rovelli, author of the 2016 bestseller

Seven Brief Lessons on Physics, says, "We don't understand the world as made by stones — by things. We understand the world made by kisses, or things like kisses: happenings."

This is a scientist talking. "Things like kisses": they are interactions among "stones." They involve

interrelationships.

One way I can visualize this is to think about musical scales. DO-RE-MI-FA-SOL-LA-TI-DO is how we represent any of the major scales. There are also minor scales, slightly different, but most of the music we hear, sing, and hum is in one of the major scales. Here is a list of the various notes on a piano that DO can represent:

- C

- C sharp or D flat

- D

- D sharp or E flat

- E

- F

- F sharp or G flat

- G

- G sharp or A flat

- A

- A sharp or B flat

- B

You can sing any DO-RE-MI-FA-SOL-LA-TI-DO song using any of these piano notes as DO. It all depends on what your most comfortable vocal range is. Whatever note you choose as DO, your audience's ears will automatically figure out which other notes are being used as which stations in a DO-RE-MI-FA-SOL-LA-TI-DO major scale.

That's because of what musicians call "intervals." For example, the interval between the DO tone and the RE tone is called a "whole-tone interval," as is that between RE and MI. But that between MI and FA is just a "half-tone interval," as is that between TI and DO. The ear automatically takes into account where in the musical scale the two half-tone intervals fall, and in so doing the ear just naturally figures out which note is DO, the "tonic" of the major scale.

In fact, the ear does not need its possessor to have studied music theory or to have learned any of its terminology, to be able to do this. It just naturally has this ability. And because it just happens to have it means that the

intervals between the notes of the DO-RE-MI-FA-SOL-LA-TI-DO are what the scale is

actually made of.

Most of the adjacent notes, such as DO and RE, represent whole-tone intervals, as I say. But the MI-FA interval and the TI-DO interval are both half-tone intervals. It is the positioning of the two half-tone intervals in the scale that tips off the ear that the scale is major and not minor. The individual piano notes

assigned to DO, RE, MI, FA, SOL, LA, TI, and DO are therefore of secondary importance. That's my whole point here.

To prove this to yourself, try singing as song like "I've Been Working on the Railroad." Then try singing it in a higher or lower key — which is the same thing as assigning a different note as DO. For example, if you first sing the song in the key of C major, you are accordingly assigning the piano note C as DO. If you then raise the song to the key of D major, then the piano note D becomes DO. Yet — and here's the important thing — your audience will immediately know that you are singing

exactly the same tune: "I've Been Working on the Railroad."

This works because it is the intervals'

interrelationships that count, not the individual notes or pitches themselves. It is these interrelationships that make the melody identifiable.

This little exercise in singing a well-known tune in different keys illustrates the principle underlying the philosophy I'm calling "relationalism." This philosophy is somewhat different from "personalism," in that in personalism it is the individual entity that is the irreducible constituent of our experience.

The irreducible constituent in personalism is accordingly

not the relationships. But the relationalism I'm proposing has it that the relationships human individuals establish among themselves or with other worldly entities — such as animals — are the real stuff of our lives.

In brief: I'm saying

relationships are primary ... not individual persons, animals, or other worldly entities.

*****

Another example of relationalism is the seesaw:

It's basically a plank balanced upon a fulcrum. Think of what a seesaw would be without a fulcrum in the middle. Basically, it would be just a plank lying on the ground.

Or, think about what a fulcrum would be without the plank. Actually, I don't know what we would call it, perhaps an "upright pointy thing." It's a fulcrum

only when there's a plank balanced upon the upright pointy thing.

So it's the relationship between the plank and the fulcrum that constitutes the entity we call a seesaw.

The plank, in turn, is made of wood. It came from a tree. That tree was once made of biological cells. Those cells of the living tree once, before the tree was cut down, had various important interrelationships among themselves. Again, it's only when the cells — or, at a lower level, the constituent atoms of the "stuff" that living cells are made of — are in the proper relationship that there's a thing that we speak of as a tree.

If we squint our philosophical eyes and look at the atoms, the cells, the tree, the plank, the fulcrum, or the seesaw in just the right way, we can see that the relationships, and not the entities that make up the constituent "stuff" of the individual entity, that are primary here. This is what the philosophy I call relationalism is all about.

*****

And don't get me wrong: I'm

not saying that relationalism doesn't — as, obviously, does personalism— affirm "the infinite uniqueness and depth of each person." It does. Just as one rendition of "I've Been Working on the Railroad," or any one particular instance of a seesaw, is uniquely distinguishable from every other rendition, every individual set of interrelationships among the constituents of a particular human body is uniquely distinguishable from every other.

So if you find you "get" personalism and don't "get" relationalism, then by all means take the former to heart and ignore the latter.

But if you feel drawn to relationalism, if not so much to personalism, there's nothing wrong with that, either.

|

| Martin Buber |

In fact, look back at certain ideas Mr. Brooks incorporates into "

Personalism: The Philosophy We Need." Specifically, the ideas of "I-Thou" and "I-It." These ideas come from Martin Buber's 1923 book

I and Thou.

The

Wikipedia article on Buber's book says:

Buber's main proposition is that we may address existence in two ways:

- The attitude of the "I" towards an "It", towards an object that is separate in itself, which we either use or experience.

- The attitude of the "I" towards "Thou", in a relationship in which the other is not separated by discrete bounds.

One of the major themes of the book [Wikipedia continues] is that human life finds its meaningfulness in relationships. In Buber's view, all of our relationships bring us ultimately into relationship with God, who is the Eternal Thou.

Wow! Buber's book and the ideas which it expresses are super-abstruse. There's no getting around that. In fact, I first tried to read Buber's book when I took a "Philosophy of Man" course at Georgetown University back in 1965 or '66. Though it was assigned reading, I got a little way into the book and gave up. I had no idea what the man was talking about!

Decades later, I came back to the book and found I could at last grasp it. Still and all — just as Mr. Brooks alludes to when he says that "to see each other person in his or her full depth ... is astonishingly hard to do" — I freely admit I still fail what I might call the "Buber test" about 99% of the time.