|

| Elizabeth Breunig |

|

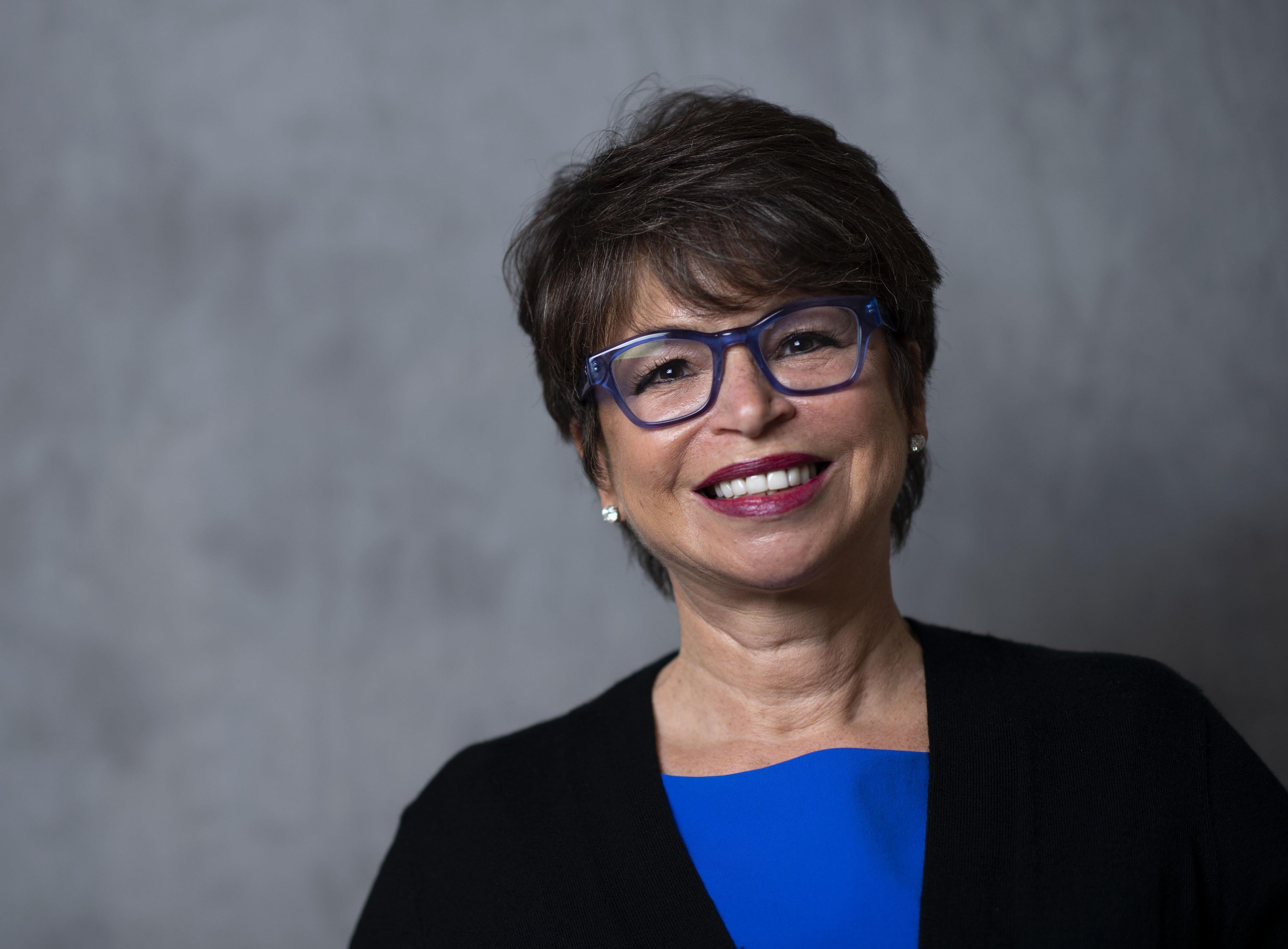

| Valerie Jarrett |

Anyway, ABC-TV network immediately cancelled the "Roseanne" sitcom series. ABC is owned by Disney, whose CEO is Bob Iger. President Donald Trump responded to the Roseanne Barr controversy by tweeting:

"Bob Iger of ABC called Valerie Jarrett to let her know that 'ABC does not tolerate comments like those' made by Roseanne Barr. Gee, he never called President Donald J. Trump to apologize for the HORRIBLE statements made and said about me on ABC. Maybe I just didn't get the call?"

|

| Samantha Bee |

Columnist Breunig writes:

There are all kinds of reasons these vindictive cycles of provocation and retribution are bad news for societies in general but democracies in particular; such was the source of much early-republic fretting about factionalism. They’re undoubtedly bad lessons in civic virtue, especially if we still purport to be something like a liberal democracy, whose key tenet is tolerance — a tough asset to claim if you’re perpetually scanning the discursive horizon for things to be disruptively furious about. But they’re worse than that. They are terrible moral lessons, and they make us into bad people.

... the habit we’re in of waging small-scale wars via celebrity censures has made us nearly incapable of really holding our allies accountable or of really forgiving our enemies. If forgiveness had a face, it would be hideous to us now; to the degree that beauty is a matter of socially constructed taste, we wouldn’t be able to look at forgiveness without revulsion. Forgiveness means having the technical right to exact some penalty but electing not to pursue it. This breaks the cycle of retribution with unearned, undeserved mercy. The face of forgiveness is bruised because it bears its own injuries with grace. So doing permits the cycle of retribution to go no further. It is a hard thing, but necessary, if huge numbers of strangers are going to live peacefully together.

Breunig's take on all this is spot on. Yet I'd add this comment: there's been a conflation of the "who" and the "what" of transgressive behavior. In fact, the "who" now (forgive me) trumps the "what."

Think about some of the other transgressions we've witnessed, albeit from a distance. Take what Bill Cosby was recently convicted of. You probably can recite the "what" of the wrongdoing involved. But five or ten years from now there will be lots of people who, when they hear the name Cosby, will realize he did something bad. But ask them what that something was, and I'll bet half of them won't be able to give you a precise answer.

Take Bill Clinton. As president, he was impeached by Congress for ... what? Yes, he had a sexual liaison with a young woman serving in the White House as an intern. But did you say that, or did you say the correct answer: two charges, one of perjury and one of obstruction of justice?

Or take President Nixon, who resigned because he was about to be impeached ... for what?

We tend to remember the "who" and lose track of the "what," no?

I think all this bears upon the definition of a word which Elizabeth Breunig uses: "strangers." There was a time when we put all people other than ourselves into two categories: people we had encountered face to face, and total strangers. But now there are all sorts of people who, like Roseanne Barr or Samantha Bee, we've never met face to face, and yet we may feel as if we have had some sort of relationship with them. We call such people "celebrities."

When a celebrity misbehaves, it registers with us bigtime. Five or ten years later, the name of the celebrity invokes an image of being bad ... although we may not be able to recall what bad things he or she did.

It's a key thing that we know both the "what" and the "who," and in our recollections the "who" often trumps the "what."

Think about what happens when a Roman Catholic goes to confession. The individual enters a small enclosure called a confessional. On the other side is another small enclosure, in which sits a priest. There is a small window between the two enclosures, but it's covered by a grille such that the priest can't see who is in the other side of the enclosure. The penitent, as that person in the other side is called, asks the priest to forgive the sins he or she lists. The priest does so, and the penitent vacates the confessional. The priest never knows the "who," only the "what."

When it comes to the sins of a celebrity today, we always find out the "who" as well as the "what."

Furthermore, most of us identify with our celebrities, or at least with certain of them. When we encounter a celebrity, we tend to form an imaginative bond with them. If the celebrity then misbehaves, our reaction to the "what" is deeply colored by our reaction to the "who."

|

| John Lennon |

For example — I'm showing my age here — when I was in my teens I identified strongly with John Lennon of the Beatles. When it came out that John had done addictive drugs and had cheated often on his first wife, I reacted in a negative direction. Put the way Elizabeth Breunig would put it, I was unable to forgive John Lennon for some of the "bad" things he had done. For me, the "who" of his misbehavior trumped the "what."

No comments:

Post a Comment