One reason I'm reconsidering is a Ross Douthat column that recently appeared in The New York Times, "Clarence Thomas’s Dangerous Idea. Does anything link the eugenics of the past to abortion today?"

As can be intuited by reading my previous blog post, "Contraception, Pregnancy and Abortion," I posted it in hopes that women who might become unintentionally pregnant and consequently opt to undergo an abortion ought to instead take advantage of free contraceptives in various forms, including pills, IUDs, and implants. These forms of contraception are now available without monetary cost to almost all women who have health insurance.

|

| Ross Douthat |

I don't claim to know the entire set of reasons why the Church opposes contraception, but one of the reasons seems to be the historical connection of contraception with the philosophy of eugenics.

Eugenics was a movement that proposed "a set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population by excluding (through a variety of morally criticized means) certain genetic groups judged to be inferior, and promoting other genetic groups judged to be superior."

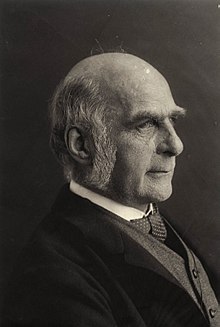

|

| Sir Francis Galton |

The eugenics movement was co-opted in the 1930s and '40s by Nazi Germany under Adolf Hitler. After the Nazis lost World War II, eugenics fell quickly out of favor in the West. But Wikipedia says:

Since the 1980s and 1990s, with new assisted reproductive technology procedures available, such as gestational surrogacy (available since 1985), preimplantation genetic diagnosis (available since 1989), and cytoplasmic transfer (first performed in 1996), fear has emerged about the possible revival of a more potent form of eugenics after decades of promoting human rights.

|

| Clarence Thomas |

Criticizing his fellow justices’ decision to block part of an Indiana law that banned abortion based on sex, race or disability, Clarence Thomas performed a public service: He brought two competing historical narratives into contact with one another, on an issue where ideological arguments often pass like trains in the night.

|

| Margaret Sanger |

Douthat extends the Thomas argument by "dividing progressive reproductive policy into three historical stages, with attitudes changing substantially but older impulses lingering in each new dispensation":

- The eugenic period per se.

- The population control period — with the promise that poorer communities and countries could be uplifted, not just culled, by reducing birthrates, and that such reductions would save the world from famine, plague and war.

- The contemporary period, in which feminist arguments predominate over the male-dominated rhetoric of the previous period, and reproductive policy is understood primarily in terms of female liberty and general sexual emancipation.

Yet even in the contemporary period there is an after-image of eugenic thought, and Thomas’s point about how legal abortion appears, in the aggregate, to act in racist and eugenic ways [can] be taken as an indicator that something more than just emancipation is at work."

Says Douthat, "In practice, liberal technocracy still has a 'solve poverty by cutting birthrates' bias inherited from a population-panic age, and abortion-rights rhetoric still has a way of sliding into Malthusian fears about too many poor kids in foster care. In practice the medical system strongly encourages abortion in response to disability, with predictable results. In practice Planned Parenthood clinics are in the abortion, not the adoption business — and the disparate impact of abortion on black birthrates is shaped by that reality and others, not just by free choice.

The "disparate impact of abortion on black birthrates" is something pro-choice feminists don't have much to say about, and it's one of the reasons I'm now coming out of the closet about my true feelings about whether abortion-on-demand and, indeed, the use of contraceptives — which don't really seem to have done much to end unplanned and unwanted pregnancies — ought to be considered righteous social policy.

No comments:

Post a Comment